|

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2013 |

Who Was Horst Wessel ?

As a teenager Horst Wessel was a leader among the youth group of the German National People’s Party, a conservative nationalist party.

He would often lead the group into brawls against Communists, but when the organization began viewing him as too extreme he became more involved with the National Socialists and the Stormtroopers (the SA).

Eventually in 1926, he abandoned his studies of law at Berlin’s Friedrich Wilhelm University to become a full-time Stormtrooper; and also to develop more of an understanding of workers’ problems and to protect lower class Germans from the Red Terror and Communist intrusions.

Now, as a leader of the SA, he often made speeches and led marches and fights against Communists in the streets.

While Berlin was a mainly Liberal and Communist city, with his charisma Horst Wessel began winning over the support and votes of many Berliners for the National Socialists.

The Judeo-Communists did everything they could to thwart Wessel’s influence, including killing SA members, and also spreading lies about Horst Wessel, saying he was originally a street beggar, a thief, and even a Berlin pimp.

Eventually Wessel became too much of a threat, so the Communist Party decided to assassinate him.

On the night of January 14, 1930 Horst Wessel opened the door to a Communist assassin who shot him in the face.

Wessel was rushed to the hospital, and would survive for forty days before passing away.

During those forty days he was frequently visited by Joseph Goebbels and SA members. Goebbels describes his experience of this in the essay below tiled “Raise the Flag High”

Bismarckjugend organized men and women between the ages of 14 and 25.

By 1928, the organization had 800 local organizations around Germany.

Its total membership had reached 42,000, making it the second largest youth movement in the country at the time (after the SPD Socialist Worker Youth, Sozialistische Arbeiter-Jugend).

Generally the movement had a stronger appeal in Protestant areas.

Strongholds included Berlin, Magdeburg, Hesse, Thuringia, Lower Saxony, Pomerania, Württemberg and Hamburg.

Most of the members came from bourgeois or noble families, however the single largest affiliate body of the movement, the Bismarck League Berlin, had an overwhelmingly working class membership.

As of 1922 the Bismarck League Berlin had around 6,000 affiliates, approximately 80% from working class families.

On 19 April 1926 (i.e. start of the summer semester) Horst Wessel enrolled at the Friedrich-Wilhelm (now Humboldt) University in Berlin (see right) to study law, and at the same time became a member of the student corporation Corps Normannia.

On 19 April 1926 (i.e. start of the summer semester) Horst Wessel enrolled at the Friedrich-Wilhelm (now Humboldt) University in Berlin (see right) to study law, and at the same time became a member of the student corporation Corps Normannia.

On 7 December 1926 he joined the NSDAP (membership no. 48 434) and at the same time Standarte I of the Berlin SA in Bötzow Quarter (Prenzlauer Berg).

On 7 December 1926 he joined the NSDAP (membership no. 48 434) and at the same time Standarte I of the Berlin SA in Bötzow Quarter (Prenzlauer Berg).

He felt that in the NSDAP/SA he could satisfy his radical political appetite.

Initially he was involved with stewarding SA meetings and what were termed “propaganda marches”, as well as distributing leaflets, etc.

In December 1926 Goebbels was made Gauführer/Gauleiter of Berlin for the Nazi party with the task of the “Conquest of Red Berlin”, and at the beginning of 1927, to raise the profile of the NSDAP/SA in Berlin, organized provocative meetings and marches to draw out the opposition which led to street fights with Communists and police, etc.

This action in turn led on 6 May 1927 to the banning of the NSDAP and its attendant organizations in Berlin till 31 March 1928.

After the lifting of the ban in March 1928 the SA underwent reorganization and restructuring under its new chief of staff von Pfeffer.

Berlin now had five Standarten comprised of ca.800 men.

Horst Wessel became attached to Sturm 1 Alexanderplatz (part of Standarte IV Berlin Central and North).

On 1 May 1929 Horst Wessel took over the leadership of SA-Trupp 34 (Friedrichshain District, i.e. near his home).

On 4 May Trupp 5 (Königstor District) was disbanded; Horst Wessel's Trupp then received its number, i.e. 5.

In consideration of the dramatic rise in the membership of Horst Wessel's new Trupp (from ca.30 when he took over to 83 two weeks later, and ca. 250 at the time of his death in Feb.1930), evidently due to Wessel's oratorical talents developed during his time with the Wiking-Bund, Trupp 5 on 19 May 1929 was promoted to Sturm 5 as an independent unit subject only to the SA leadership in Berlin.

Its area of operations was to be Friedrichshain (north and west of Alexanderplatz).

Its area of operations was to be Friedrichshain (north and west of Alexanderplatz).

In August 1929 Horst Wessel, in an unusual move deliberately designed for maximum propaganda effect, founded a Schalmeienkapelle (see right), or shawm band, within his own area – Wessel himself played the shawm (see left) - a type of oboe popular in Germany.

At about that time Horst Wessel (see right) made it his business to visit bars and cafés around and about the Alexanderplatz and adjacent Scheunenviertel to hold discussion sessions with the clientèle in the hope of obtaining converts.

At about that time Horst Wessel (see right) made it his business to visit bars and cafés around and about the Alexanderplatz and adjacent Scheunenviertel to hold discussion sessions with the clientèle in the hope of obtaining converts.

In this respect he appears to have had some success.

At the start of the 1929 winter semester (October) Horst Wessel, due to his full time commitment to the SA and the Hitler cause, gave up his law studies.

On 22 December Horst Wessel's younger brother Werner was killed on a skiing trip in the Riesengebirge.

Feeling responsible, as he had seemingly talked his brother into taking the trip Wessel became quite depressed.

At ca.22.00hrs that evening Horst Wessel answered the door only to receive a gunshot wound to the mouth from a certain Alfred (Ali) Höhler, by all accounts a pimp and deputy leader of the Communist 3rd Bereitschaft (squad) in the Mulackstraße (about 20 min. walk away).

Horst Wessel was taken to St. Joseph's Hospital (see left) where he died on 23 February and buried on 1 March 1930 in the St. Nicolai Friedhof, Central Berlin.

The reason for the attack was for long years a matter of dispute. It is generally believed that it was a political murder.

The outcome of the affair was, through Goebbels’s efforts, given Horst Wessel's high profile in the Berlin SA, the elevation of Horst Wessel to the status of martyr, and the exaltation of his song “Die Fahne hoch!” as the offical Weihelied (song of consecration) for the Nazi party, and after 30.01.1933 as the official second part of the National Anthem after the Deutschlandlied.

Horst Ludwig Wessel was buried on 1 March in the Nikolaifriedhof, in Prenzlauer Allee.

Horst Ludwig Wessel was buried on 1 March in the Nikolaifriedhof, in Prenzlauer Allee.

It was reported that 30,000 people lined the streets to see the funeral procession (see left and right).

Goebbels delivered the eulogy in the presence of Hermann Göring and Prince August Wilhelm of Prussia, son of former emperor Wilhelm II, who had joined the SA.

The Berlin district of Friedrichshain, where Wessel died, was renamed 'Horst Wessel', and a square in the Mitte district, Bülowplatz (see right), was renamed 'Horst-Wessel-Platz', as was the U-Bahn station nearby.

The Berlin district of Friedrichshain, where Wessel died, was renamed 'Horst Wessel', and a square in the Mitte district, Bülowplatz (see right), was renamed 'Horst-Wessel-Platz', as was the U-Bahn station nearby.

In 1936, the Kriegsmarine commissioned a three-masted training ship and named her the 'Horst Wessel' (see left).

Examples of German military units adopting the name of the Party's martyr in World War II include the 18th SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Division, known as the "Horst Wessel" Division (see right below),

and the World War II era Luftwaffe's 26th Destroyer (or heavy fighter) Wing (Zerst Rergeschwader 26), as well as its successor day fighter unit Jagdgeschwader 6, which was similarly named the "Horst Wessel" wing (see left).

and the World War II era Luftwaffe's 26th Destroyer (or heavy fighter) Wing (Zerst Rergeschwader 26), as well as its successor day fighter unit Jagdgeschwader 6, which was similarly named the "Horst Wessel" wing (see left).

During the Battle of Britain, one successful attack on British planes was celebrated as the name of Horst Wessel represented absolute "devotion to duty", so too would they carry on until victory.

The function of the Kampflied in the SA

Before looking more closely at Horst WesselL it is felt pertinent here to outline the function of the Kampflied in SA politics.

Practically all, if not all, SA songs before 1933 could be classed as Kampflieder, whose authors were usually members of the SA.

Given that the mass media as we know it today was at that time only in its infancy, the Kampflied still bore the important function of disseminating the philosophy and aims of any political (in this case the NS) movement, often through catchy slogans set to dynamic tunes played with much briskness and gusto. As Hans Bajer puts it:

'Das wirkungsvollste Propagandamittel für die SA war das Kampflied.

Wenn ein Sturm auf seinen häufigen Propagandamärschen singend durch die "roten" Stadtviertel zog oder an Sonntagen hinausmarschierte auf die Dörfer und Flecken, so stand das ganze Dorf im Bann der sangesfreudigen braunen Kolonnen.'

(‘The most effective means of propaganda for the SA was the Kampflied.

Whenever a Sturm on one of its frequent propaganda marches came singing through the ‘Red’ areas of the town, or marched out on a Sunday into the small villages and places, the entire village would be spellbound by the hearty singing of the brownshirt columns’)(Bajer 1939b: 586).

The messages incorporated in the songs were designed to appeal to the various sections of the community and to offer an alternative to what was perceived as the chaotic situation of the Weimar Republic:

'Das Kampflied sieht seine wichtigste Aufgabe darin, die Zeitgenossen auf die Bewegung des Führers hinzuweisen, ihnen einen neuen Glauben zu geben und das baldige Ende der augenblicklichen Not und Schmach anzukündigen.'

(‘The most important function of the Kampflied was to inform the public at that time about the Hitler Movement, to give them a new faith and to herald a quick end to the distress and ignominy of the moment...’)(Bajer 1939b: 587).

The concept of the mass movement, as promoted by the NSDAP, and the Kampflied are to be seen in close association, the latter serving the propaganda interests of the former.

In this regard it could be said that right from the very beginning, but especially towards the end of the Weimar Republic, the Kampflied was the embodiment of the song in action, or “Lyrik im Einsatz”, as the Nazis called it, to serve a given end.

The importance of the Kampflied in this context was evidently not lost on Horst Wessel either:

'Das Zaubermittel des gesungenen Liedes hatte auch Horst Wessel erkannt.

Es verging kaum ein Sturmabend, an dem er nicht ein neues Lied mit seinen Kameraden einübte, und in Berlin wußte man, daß sein Sturm die meisten und schönsten Kampflieder der Bewegung kannte.

Der sichtbare Erfolg blieb denn auch nicht aus: Horst Wessel hatte einen derartigen Andrang zu verzeichnen, daß sein Sturm 5 bald alle übrigen Berliner Stürme an Stärke überflügelte [cf. §1.1.above][...]. Das Kampflied war der Gradmesser für das Vorwärtsstürmen der Bewegung'

(‘Horst Wessel was also well aware of the magical impact songs could evoke. Hardly an evening passed with his Sturm when he would rehearse a new song with his comrades, and in Berlin it was common knowledge that his Sturm knew the greatest number of the Movement's best Kampflieder.

The inevitable success was for all to see: Horst Wessel scored such a success that his Sturm 5 soon surpassed all other Berlin Stürme in strength of numbers.

The Kampflied was the gauge whereby the Movement's surge forward in popularity was measured’)(Bajer 1939b: 587).

History of "Die Fahne hoch!" before 1945

According to Engelbrechten & Volz (1937: 90-91) “Die Fahne hoch!” was composed by Horst Wessel on the evening of 24 March 1929 following the first march made by the Berlin SA (Standarte IV - to which Horst Wessel then belonged) on that day via Bülowplatz (later Horst-Wessel-Platz, now Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz) and past Karl-Liebknecht-Haus.

As with other SA marches the intention, as mentioned earlier, was to provoke and draw out the opposition, and in expectation of an attack by Communists the Standartenführer is said to have given the order “die Reihen dicht geschlossen!” (‘the ranks tightly closed!’), which, according to Engelbrecht & Volz and “Rüdiger” (1933 quoting from a lecture delivered by Ingeborg Wessel), inspired Horst Wessel that night to compose his song.

The need for a song with a vibrant melody and an e'asy-to-learn and sing' text, that could be sung at the end of a meeting or march, as a balance to the “Internationale” of the Communists, was felt to be lacking in the SA repertoire (cf. “Rüdiger” 1933:).

The story goes that it was first sung at an NSDAP mass meeting in the Neue Welt-Halle some two months later (between 19-26 May 1929), at which Dr Goebbels was to speak. Standarte IV and the newly created Sturm 5, whose leader was Horst Wessel, stood behind the curtain waiting for the signal that Goebbels had ended his speech.

The applause had not yet died down when the curtain rose and the new song echoed round the hall ‘from 400 young throats’.

By the time the fourth quatrain (i.e. the first repeated) was reached the whole meeting had joined in the song (“Rüdiger” 1933).

According to “Rüdiger” and Engelbrecht & Volz (1937), the song was heard first on the streets of Berlin on 26 May 1929 (by Standarte IV and Sturm 5) following a æpropaganda march” to Frankfurt-an-der-Oder and found currency at the NSDAP Parteitage in Nürnberg 1-4 August that same year.

It was first sung at the Sportpalast, Berlin, at a mass meeting of the NSDAP on 7 February 1930.

After Wessel's death the song had already before 30.01.1933 took on the function of a Weihelied for the NSDAP, and after the “Machtergreifung” was elevated to the status of Party Anthem and as such played as an adjunct to the National Anthem, the Deutschlandlied (Oertel 1988).

However, Goebbels (Tagebuch 30.06.1937, quoted by Oertel) was of the opinion, somewhat belated, that in such circumstances the text would need to be modified, as it was felt to be unsuitable as it stood.

As it turned out, no modification took place - nor was it deleted (“Aber abschaffen kann man es nicht” (‘but one cannot do away with it’) - 30.06.37), and the text remained unaltered till the song fell into disuse after the end of the war.

As to the manner in which the song was to be sung, a regulation attached to a printed version of the song in 1934 made it clear that the right arm had to be raised (i.e. in a Hitler salute) whenever the first and fourth verses were sung.

In the pre-war years songs such as Horst WesselL, Deutschlandlied, and other popular patriotic and NS songs seemingly found free expression among street musicians, or in Gaststätten (bar restaurants), for example.

But in February 1940 as part of the official “Schutz nationaler Symbole und Lieder” (‘Protection of National Emblems and Songs’; in the context of the war situation) Goebbels, in association with the Interior Ministry, ordered the banning of such songs, including Horst Wessel Lied, in such as the above mentioned places, except on officially sanctioned special occasions.

The ban also covered the use of the melody with other texts.

In the case of the Deutschlandlied and the Horst-Wessel-Lied, these could no longer be played/sung in potpourris.

The Text

Although the song is believed to have been composed in March 1929, the first printed version of the text, so far as is known, did not appear till six months later in a supplement to Der Angriff Nr. 38 Berlin, 23 September 1929 entitled “Der Unbekannte SA-Mann”.

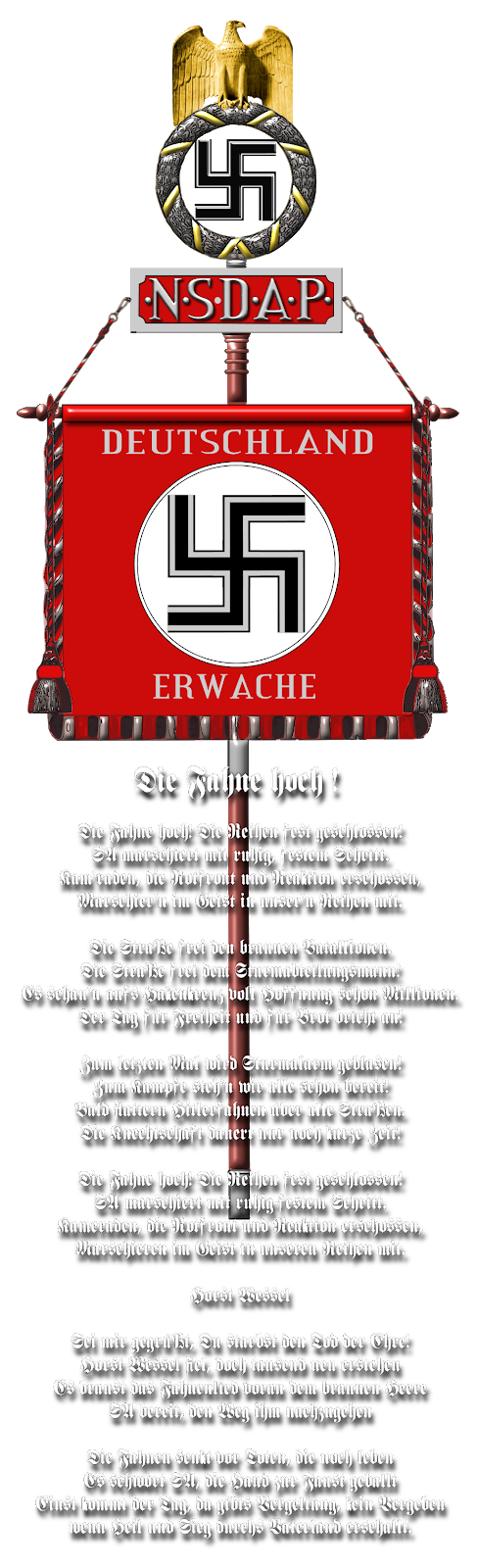

The text (see below) itself bears the title “Die Fahne hoch!”

This seems to be the original version of the song. The text is comprised of four quatrains, the fourth being a repeat of the first.

('The flag high, the ranks tightly closed. SA marches pluckily at a firm pace. Comrades, shot dead by Red Front and Reaction, march in spirit within our ranks (also stanza 4).

The street clear for the brown battalions, the street clear for the SA man. Already millions are looking to the swastika full of hope. The day of freedom and bread is dawning.

For the last time the rollcall has sounded, we are all ready for the fight. Soon Hitler flags will fly over barricades; the servitude will not last long now').

It is interesting to note that there is no anti-semitic sentiment in the text.

The tenor of the song evokes a certain unity: with the flag raised on high as a symbol of the movement and its aims the troops (SA) in tightly closed ranks, including those who march in spirit (a notion of the dead assisting the living in the cause), remove the opposition, and in doing so offer a signal of hope to (as they see it) a beleaguered populace.

The “final battle” comes which the movement is confident of winning, after which the servility (as it is perceived) under which the country is suffering will be removed and a new dawning will arrive.

This motif of achieving victory through strife (common in songs extolling revolution) - in this context “for a New Germany” - is a reoccurring theme in many SA songs, e.g. Brüder in Zechen und Gruben (ca. 1927), Volk ans Gewehr (1931).

Metre and Linguistic Structure

The metre used is essentially iambic, with each quatrain having the pattern 51 5 61 5.

It falls into the pattern of the so-called “long metre”, reminiscent of the type: “O Danny boy, the pipes, the pipes are calling...”. A caesura occurs in each line after the second foot. ( • = short; - = long).

• - | • - || • - | • - | • - | •

Die Fahne hoch! Die Reihen fest geschlossen

|• - | • - || • - | • - | • -

S A marschiert mit mutig festem Schritt

| • - |• - || • - | • -|• - | • - | •

Kam'raden, die Rotfront und Reaktion erschossen

| • - | • - || • - | • - | • -

Marschieren im Geist in unseren Reihen mit

In “free metre”, i.e. in normal speech rhythm, we would expect the following:

• - • - • - • •/- • - •

Die Fahne hoch! Die Reihen fest geschlossen

- - • - • - • - • -

S A marschiert mit mutig festem Schritt

- - • • • - • - • - • - •

Kam'raden, die Rotfront und Reaktion erschossen

• - ( • )• - • - • - • -

marschieren im Geist in unsren Reihen mit

The melody (cf. § 3.5. below), however, has a slightly different schema.

It is simple in structure, in 4 4 (Common) time; the main stress/beat falls on the first element of the bar, with decreasing stress on the third, second, and fourth elements in that order, i.e. = 1, + 2, - 3, • 4 (the vertical single stroke | would here represent bar division). Thus we have:

|+ - • | = || • | = + - • | = -

Die Fahne hoch! Die Reihen fest geschlossen

+ - • | = || • | = + - • | =

S A marschiert mit mutig festem Schritt

+ - • | = || + - • | = + - • | = -

Kam'raden, die Rotfront und Reaktion erschossen

+ - • | = || • | = + - • | =

Marschieren im Geist in unseren Reihen mit

The result is that the main emphasis, resulting in elongated stress, occurs before before the caesura.

Given that the song is appellative to a specific group (i.e. the SA) recognisable slogans and Aufrufe would therefore be expected in places of emphasis, e.g. before the caesura: (I.1.) Die Fahne hoch! (I.2.) S A marschiert, (II.1/2) Die Straße frei! (III. 1/2.) Zum letzten Mal.

In the third line, the longest, the main emphasis comes on the second bar, with the highpoint reached in (I.3.) die Rotfront (which would be a term of abuse), (II.3.) Hakenkreuz, (III.3.) Hitlerfahnen, all meeting the appellative requirements of the song.

In I.3, however, the rhythm of the line requires unnatural stress on die (long instead of short). In II.4. Freiheit and III.4. dauert are split by the caesura, viz. Frei || heit, dau || ert, thus giving an unnatural and awkward emphasis, avoidable if sung in free rhythm.

As noted by Kurzke (1990: 128-29), Zum letzten Mal is reminiscent of the “last battle” motif found in La Marseilles and the Internationale, while the slogans Der Tag für/der Freiheit und für Brot bricht an (i.e. “Freiheit und Brot”) and Die Knechtschaft dauert nur noch kurze Zeit recall the concepts of “Knechtschaft”, “Reaktion”, along with the “Fahne” and “Kampf” metaphors, in 19th century Communist/Socialist Kampflieder.

There is also a certain amount of internal rhyme and alliteration used for effect:

I.2. marschiert mit mutig festem Schritt

I.3. Rotfront und Reaktion erschossen

I.4. im Geist in unseren Reihen mit

II.3. Es schaun aufs Hakenkreuz voll Hoffnung schon Millionen

II.4. für Freiheit und für Brot bricht an

III.1. Mal...geblasen

III.3. Bald flattern Hitlerfahnen über allen Straßen/Barrikaden

In addition the frequent re-occurrence of the /ai/ diphthong, through its high phonological profile, gives a greater zest and vitality to the song: Reihen, Geist, Frei, Freiheit, bereit, Zeit.

It is clear that some considerable thought has gone into fashioning it to achieve a desired effect.

We have seen the emphatic use of slogans and Aufrufe, found in lines 1, 2, and 4.

In contrast the third line of each stanza, i.e. the longest one containing six feet, makes use of the three tenses, past, present, and future, to give a sense of continuation and momentum to the song: (past) Kameraden, die Rotfront und Reaktion erschossen, (present) Es schaun aufs Hakenkreuz voll Hoffnung schon Millionen, (future) Bald flattern Hitlerfahnen über allen Straßen (cf. also Kurzke 1990: 128).

Along with skilful use of alliteration and internal rhyme, as we have seen, the final result cannot be said to be entirely devoid of some literary merit and quality.

The Melody

Melodic analysis

Melodies A and B are identical. The pattern of the phrases is typical of the Lied style.

In B bars 2b-3a correspond exactly to the opening and imply a sequential phrase, but 1b-2a and 3b-4a negate this. Bars 4b-6b are characteristically at the highest pitch, and with the final phrase returning to the key note.

3.5.3.2. Implied harmonic framework

An implied harmonic framework could be sketched as follows:

bar 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

implied I IV V I I IV Ic V I

Harmony

It is quite possible to use only the three basic chords of I, IV, and V to harmonise the melody satisfactorily. Bars 3-4 are sequential to bars 1-2, as was implied, but not fully carried out in the melody.

The final cadence of Ic V I is characteristic of Northern European music from the Baroque period onwards.

There is no sense of implied modulation.

Rhythmic structure

The rhythmic structures are very similar, with only a small modification in B.

Each phrase begins on an anacrusis, leading to a longer note on the first beat in bars 1, 3, and 7. Bar 5 reflects this but with a dotted note of shorter value. However, bar 5 has greater movement, with a note on each half-beat.

Bars 6b-8a return to the original pattern.

B uses more dotted rhythms, as in bars 1b, 3b, 5b, and 7b.

In Western European tradition these often have a military implication of an heroic nature, cf. Beethoven's "Eroica" Symphony (No. 3), Slow Movement - Funeral March.

In an editorial in the Völkischer Beobachter, Alfred Rosenberg (see right) wrote of how Horst Wessel was not dead, but had joined a combat group that still struggled with them; and afterwards, members of the NSDAP spoke of how a man who died in conflict had joined "Horst Wessel's combat group" or were "summoned to Horst Wessel's standard."

In an editorial in the Völkischer Beobachter, Alfred Rosenberg (see right) wrote of how Horst Wessel was not dead, but had joined a combat group that still struggled with them; and afterwards, members of the NSDAP spoke of how a man who died in conflict had joined "Horst Wessel's combat group" or were "summoned to Horst Wessel's standard."

Eventually Wessel became too much of a threat, so the Communist Party decided to assassinate him.

On the night of January 14, 1930 Horst Wessel opened the door to a Communist assassin who shot him in the face.

Wessel was rushed to the hospital, and would survive for forty days before passing away.

During those forty days he was frequently visited by Joseph Goebbels and SA members. Goebbels describes his experience of this in the essay below tiled “Raise the Flag High”

______________________________________

An essay by

Dr Paul Joseph Goebbels

It was late in the evening and I was enjoying the rare pleasure of reading a good book.

I was relaxed and at ease.

The telephone rang.

I picked up the phone with trepidation.

Trembling with fear, I asked: “Dead?” “No, but there is no hope.”

I felt as if the walls were collapsing around me. It was unbelievable. It cannot be!

A few days later I step into the small hospital room on the ground floor and am shocked by the sight.

A bullet in the head has done terrible damage to this heroic lad.

His face is distorted. I hardly recognize him.

But he is happy. His clear, bright eyes shine, though we cannot talk for long.

The doctor has ordered him to keep calm. He only repeats a few words: “I am happy.”

He does not need to say it. One sees it by looking at him.

His young, bright smile overcomes the blood and wounds. He still believes.

I sat by his bed on a Sunday afternoon as streams of visitors came until evening.

One can hope. He is improving. The fever has dropped, the wounds healing.

He sat up part way and talked. What about? A foolish question!

About us, about the movement, about his comrades.

They stood outside his door today, and one after the other came by and raised his arm to salute the young leader for a moment.

I could not bear it otherwise! I look at his hands, which are now small and white.

His strong nose stands out in the middle of his face, and two bright eyes sparkle.

But the fever is back. He cannot eat, his strength gradually declines, though his spirit remains fresh and alert.

He is not allowed to read. He may only talk. It is hard to obey the warning look of the nurse. Will I ever see him again? Who knows! If blood poisoning does not develop, everything will be OK.

A lonely mother sits outside. Her face reflects a question. “Will he make it?”

What can one say but yes? I try to persuade myself and others.

Blood poisoning develops.

By Thursday, there is little hope. He wants to talk with me.

The doctor gives me a minute. How hard it is to walk past the death watch into the room!

He does not know how serious his condition is. But he senses it may be the last time:

“Do not go away!” he begs. The nurse relents, and he is comforted. “Do not lose hope“.

The fever comes and goes.

“The movement, too, has suffered in the last two years, but today it is hard and strong.”

That consoles him.

“Come back!” his eyes, his hands, his hot dry lips, say, as I leave with a heavy heart.

I fear I have seen him for the last time.

Saturday morning. It is hopeless. The doctor is no longer allowing visits.

He is hallucinating. He does not even recognize his own mother any longer.

It is 6:30 Sunday morning. He dies after a hard struggle.

As I stand by his bed two hours later, I can not believe that it is Horst Wessel.

His face is yellow, the wounds still covered with white band aids.

Stubble shows on his chin. The halfopen eyes stare glassily into the eternity that we all face. The small cold hands lie in the midst of flowers, while and red tulips and violets.

Host Wessel has passed on. His mortal remains have given up struggle and conflict.

Yet I can almost physically feel his spirit rise, to live on with us.

He believed it, he knew it. He himself put it in words:

He “marches in spirit in our ranks.”

One day in a German Germany, workers and students will march together singing his song. He will be with them. He wrote it in a moment of ecstasy, of inspiration.

The song flowed from him, born of life and bearing witness to that life.

The brown soldiers are singing it across the country.

In ten years, children will sing it in the schools, workers in the factories, soldiers on the march.

His song makes him immortal.

That is how he lived, that is how he died.

A wanderer between two worlds, between yesterday and tomorrow, between that which was and that which will be.

A soldier of the German revolution!

Once he stood with his hand on his belt, proud and upright, with the smile of youth on his red lips, always ready to risk his life.

That is how we will remember him.

I see endless columns marching in spirit. A humiliated people rises up and begins to move. An awakened Germany demands its rights: Freedom and prosperity!

He marches behind them in spirit. Many of them will not know him. Many will have gone where he now is. Many others will have come.

He strides silently and knowingly with them.

The banners wave, the trumpets sound, the pipes sound, and from a million threats the song of the German revolution resounds: “Raise the flag high!” (This was the opening line to the “Horst Wessel Song,” a poem he had written that became the Nazi Party anthem.)

'The Flag High ! The flag high ! The ranks tightly closed! The SA march with bold, firm steps. Comrades shot by the Red Front and reactionaries March in spirit in our ranks. Clear the streets for the brown battalions, Clear the streets for the stormtroopers! Already millions look with hope to the swastika. The day of freedom and bread is dawning! Roll call has sounded for the last time! We are all already prepared for the fight! Soon Hitler's flag will fly over the barricades.

Our slavery will soon end! The flag high! The ranks tightly closed! The SA marches with a bold, firm pace. Comrades shot by the Red Front and reactionaries March in spirit in our ranks.'

Our slavery will soon end! The flag high! The ranks tightly closed! The SA marches with a bold, firm pace. Comrades shot by the Red Front and reactionaries March in spirit in our ranks.'

______________________________________

Introduction

Originally entitled “Die Fahne hoch!” from the opening phrase the “Horst-Wessel-Lied” (“Horst Wessel Lied/Song” in English), as it quickly came to be known was composed by SA-Mann Horst Wessel, seemingly in March 1929.

After Hitler's coming to power on 30 January 1933 it formed the second part to the National Anthem after the Deutschlandlied (“Deutschland über alles”) and remained as such until the demise of the Third Reich in May 1945.

The song can still evoke an emotional response, favourable or unfavourable, even today from many in Germany who experienced the period of the Third Reich.

Under §86a of the Strafgesetzbuch (Criminal Code) it is an offence punishable in law in Germany today to sing or play the melody of the song even with an unfamiliar text.

Much has been written about the Horst-Wessel-Lied since the time of Horst Wessel's death on 23.02.1930 down to the present.

|

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2013 |

his life and times in brief

Horst Wessel, born Horst Ludwig Wessel (see right) on 9 October 1907 in Bielefeld, was the first of three children (Ingeborg and Werner being the other two) to Pastor Dr Wilhelm Ludwig Georg Wessel (see right) and Luise Margarete (née Richter).

His father's family came from the area of Oberwesertal in Hessen, his mother from a protestant family of pastors in Uerzen, Kreis Hameln.

During the period 1906-08 Pastor Wessel was incumbent at the Pauluskirche in Biele-feld (see right), and from 1908-13 ministered at the Petrikirche in Mülheim in the Ruhrgebiet.

In November 1913 Horst Wessel's father took over ministry of Berlin's oldest church, the St. Nicolai-kirche, and the family went to live in Jüdenstr. 51/52 in the former Jewish quarter of central Berlin.

After the First World War Wessel senior involved himself in conservative and nationalist politics, founding and holding the presidency of the Reichsbürgerrat.

In 1921 he took over the literary and political columns of the newly established “Große Berliner Illustrierte”.

He died aged 42 in May 1923, the family still living on at the old address.

Horst Wessel was thus brought up in a milieu of conservative/nationalist thinking which was to determine his own political direction later on.

At Easter 1914 Horst Wessel began attending the Volksschule des Köllnischen Gymnasiums in Berlin, and in 1922 he moved to the Gymnasium in Königstadt.

In the autumn of the same year he attended the Luisenstadt Gymnasium where in February 1926 he sat and passed his Abitur ('A' Levels).

In the late summer of 1922 when still only 15 he joined the Bismarckjugend (the youth movement of the Deutschnationale Volkspartei (DNVP)) and became a member of Ortsgruppe (local group).

Bismarckjugend, 'Bismarck Youth', was an anti-Marxist youth movement in Weimar Germany. Bismarckjugend was the youth wing of the monarchist German National People's Party (DNVP).

By 1928, the organization had 800 local organizations around Germany.

Its total membership had reached 42,000, making it the second largest youth movement in the country at the time (after the SPD Socialist Worker Youth, Sozialistische Arbeiter-Jugend).

Generally the movement had a stronger appeal in Protestant areas.

Strongholds included Berlin, Magdeburg, Hesse, Thuringia, Lower Saxony, Pomerania, Württemberg and Hamburg.

Most of the members came from bourgeois or noble families, however the single largest affiliate body of the movement, the Bismarck League Berlin, had an overwhelmingly working class membership.

As of 1922 the Bismarck League Berlin had around 6,000 affiliates, approximately 80% from working class families.

In March 1924 he transfered to local group “Kronprinzesin” where he set up his own “Selbstschutz” or self protection group that provided stewarding at DNVP meetings.

It was in such circumstances that Horst Wessel partook in street fights with Communists and Reichsbanner activists which was to stand him in good stead, as it were, in similar activity later with the SA.

His experiences with the Selbstschutz by all accounts developed his leadership qualities.

While still a member of the Bismarckjugend (in 1929 renamed “Bismarckbund der DNVP”) he joined, in December 1923, the more radical Wiking-Bund, a successor to the proscribed “Organization Consul”.

.png) |

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2013 |

For Horst Wessel political activity within an organization had to achieve practical results; if not it was abandoned for something else.

He was evidently not interested in hankering after times past, but in changing the present political situation, i.e. getting rid of the Weimar Republic (see right).

When the Bismarckjugend and Wiking-Bund ceased to be of use to him in that respect he left them, the former in February 1925, the latter in late autumn 1926.

On 19 April 1926 (i.e. start of the summer semester) Horst Wessel enrolled at the Friedrich-Wilhelm (now Humboldt) University in Berlin (see right) to study law, and at the same time became a member of the student corporation Corps Normannia.

On 19 April 1926 (i.e. start of the summer semester) Horst Wessel enrolled at the Friedrich-Wilhelm (now Humboldt) University in Berlin (see right) to study law, and at the same time became a member of the student corporation Corps Normannia.  On 7 December 1926 he joined the NSDAP (membership no. 48 434) and at the same time Standarte I of the Berlin SA in Bötzow Quarter (Prenzlauer Berg).

On 7 December 1926 he joined the NSDAP (membership no. 48 434) and at the same time Standarte I of the Berlin SA in Bötzow Quarter (Prenzlauer Berg). He felt that in the NSDAP/SA he could satisfy his radical political appetite.

Initially he was involved with stewarding SA meetings and what were termed “propaganda marches”, as well as distributing leaflets, etc.

In December 1926 Goebbels was made Gauführer/Gauleiter of Berlin for the Nazi party with the task of the “Conquest of Red Berlin”, and at the beginning of 1927, to raise the profile of the NSDAP/SA in Berlin, organized provocative meetings and marches to draw out the opposition which led to street fights with Communists and police, etc.

This action in turn led on 6 May 1927 to the banning of the NSDAP and its attendant organizations in Berlin till 31 March 1928.

Horst Wessel's superiors were evidently satisfied and impressed with his activities as SA-Mann, for from mid-January to the end of July 1928 he was commissioned by Goebbels (see right) to visit Vienna in order to study organizational and tactical methods of the Nazi apparatus there, especially the HJ, with a view to using any methods learned for a better structuring of the Berlin HJ on his return2.

It was during his stay in Austria that Horst Wessel became one of the most prominent supporters of the Welteislehre (World Ice Theory), or Glazial-Kosmogonie (Glacial Cosmogony) of Hanns Hörbiger (see left) - and he later popularised the cosmological theory in Germany.

|

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2013 |

click below for more information about

After the lifting of the ban in March 1928 the SA underwent reorganization and restructuring under its new chief of staff von Pfeffer.

Berlin now had five Standarten comprised of ca.800 men.

Horst Wessel became attached to Sturm 1 Alexanderplatz (part of Standarte IV Berlin Central and North).

On 1 May 1929 Horst Wessel took over the leadership of SA-Trupp 34 (Friedrichshain District, i.e. near his home).

On 4 May Trupp 5 (Königstor District) was disbanded; Horst Wessel's Trupp then received its number, i.e. 5.

In consideration of the dramatic rise in the membership of Horst Wessel's new Trupp (from ca.30 when he took over to 83 two weeks later, and ca. 250 at the time of his death in Feb.1930), evidently due to Wessel's oratorical talents developed during his time with the Wiking-Bund, Trupp 5 on 19 May 1929 was promoted to Sturm 5 as an independent unit subject only to the SA leadership in Berlin.

Its area of operations was to be Friedrichshain (north and west of Alexanderplatz).

Its area of operations was to be Friedrichshain (north and west of Alexanderplatz). In August 1929 Horst Wessel, in an unusual move deliberately designed for maximum propaganda effect, founded a Schalmeienkapelle (see right), or shawm band, within his own area – Wessel himself played the shawm (see left) - a type of oboe popular in Germany.

At that time bands of that sort were associated only with Communists and Socialists, and indeed possession of a shawm or associated instrument in the SA was forbidden, however, it evidently achieved the desired effect.

The shawm was a medieval and Renaissance musical instrument of the woodwind family made in Europe from the 12th century.

It was developed from the oriental zurna and is the predecessor of the modern oboe.

The body of the shawm was usually turned from a single piece of wood, and terminated in a flared bell somewhat like that of a trumpet.

Beginning in the 16th century, shawms were made in several sizes, from sopranino to great bass, and four and five-part music could be played by a consort consisting entirely of shawms.

All later shawms had at least one key allowing a downward extension of the compass; the keywork was typically covered by a perforated wooden cover called the fontanelle.

The bassoon-like double reed, made from the same Arundo donax cane used for oboes and bassoons, was inserted directly into a socket at the top of the instrument, or in the larger types, on the end of a metal tube called the bocal.

The pirouette, a small cylindrical piece of wood with a hole in the middle resembling a thimble, was placed over the reed—this acted as a support for the lips and embouchure.

Since only a short portion of the reed protruded past the pirouette, the player had only limited contact with the reed, and therefore limited control of dynamics.

The shawm’s conical bore and flaring bell, combined with the style of playing dictated by the use of a pirouette, gave the instrument a piercing, trumpet-like sound well-suited for out-of-doors performance.

At about that time Horst Wessel (see right) made it his business to visit bars and cafés around and about the Alexanderplatz and adjacent Scheunenviertel to hold discussion sessions with the clientèle in the hope of obtaining converts.

At about that time Horst Wessel (see right) made it his business to visit bars and cafés around and about the Alexanderplatz and adjacent Scheunenviertel to hold discussion sessions with the clientèle in the hope of obtaining converts. In this respect he appears to have had some success.

At the start of the 1929 winter semester (October) Horst Wessel, due to his full time commitment to the SA and the Hitler cause, gave up his law studies.

On 22 December Horst Wessel's younger brother Werner was killed on a skiing trip in the Riesengebirge.

Feeling responsible, as he had seemingly talked his brother into taking the trip Wessel became quite depressed.

At ca.22.00hrs that evening Horst Wessel answered the door only to receive a gunshot wound to the mouth from a certain Alfred (Ali) Höhler, by all accounts a pimp and deputy leader of the Communist 3rd Bereitschaft (squad) in the Mulackstraße (about 20 min. walk away).

Horst Wessel was taken to St. Joseph's Hospital (see left) where he died on 23 February and buried on 1 March 1930 in the St. Nicolai Friedhof, Central Berlin.

The reason for the attack was for long years a matter of dispute. It is generally believed that it was a political murder.

The outcome of the affair was, through Goebbels’s efforts, given Horst Wessel's high profile in the Berlin SA, the elevation of Horst Wessel to the status of martyr, and the exaltation of his song “Die Fahne hoch!” as the offical Weihelied (song of consecration) for the Nazi party, and after 30.01.1933 as the official second part of the National Anthem after the Deutschlandlied.

POSTHUMOUS FAME

Horst Wessel was elevated by Goebbels' propaganda apparatus to the status of leading martyr of the Nazi movement.

Goebbels himself began the process with his 17 February 1930 account of Wessel's death "Raise High the Flag!" (see below) Horst Ludwig Wessel was buried on 1 March in the Nikolaifriedhof, in Prenzlauer Allee.

Horst Ludwig Wessel was buried on 1 March in the Nikolaifriedhof, in Prenzlauer Allee.It was reported that 30,000 people lined the streets to see the funeral procession (see left and right).

Goebbels delivered the eulogy in the presence of Hermann Göring and Prince August Wilhelm of Prussia, son of former emperor Wilhelm II, who had joined the SA.

© Copyright Peter Crawford 2013

Die Beerdigung von Horst Wessel

The Berlin district of Friedrichshain, where Wessel died, was renamed 'Horst Wessel', and a square in the Mitte district, Bülowplatz (see right), was renamed 'Horst-Wessel-Platz', as was the U-Bahn station nearby.

The Berlin district of Friedrichshain, where Wessel died, was renamed 'Horst Wessel', and a square in the Mitte district, Bülowplatz (see right), was renamed 'Horst-Wessel-Platz', as was the U-Bahn station nearby.In 1936, the Kriegsmarine commissioned a three-masted training ship and named her the 'Horst Wessel' (see left).

Examples of German military units adopting the name of the Party's martyr in World War II include the 18th SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Division, known as the "Horst Wessel" Division (see right below),

and the World War II era Luftwaffe's 26th Destroyer (or heavy fighter) Wing (Zerst Rergeschwader 26), as well as its successor day fighter unit Jagdgeschwader 6, which was similarly named the "Horst Wessel" wing (see left).

and the World War II era Luftwaffe's 26th Destroyer (or heavy fighter) Wing (Zerst Rergeschwader 26), as well as its successor day fighter unit Jagdgeschwader 6, which was similarly named the "Horst Wessel" wing (see left).During the Battle of Britain, one successful attack on British planes was celebrated as the name of Horst Wessel represented absolute "devotion to duty", so too would they carry on until victory.

The martyrdom of Horst Wessel led directly to 'Das Horst-Wessel-Lied' , also known as 'Die Fahne hoch' ("The Flag On High") from its opening line, being promoted as the anthem of the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei from 1930 to 1945.

From 1933 to 1945 it was a co-national anthem of Germany, along with the first stanza of the 'Deutschlandlied'.

From 1933 to 1945 it was a co-national anthem of Germany, along with the first stanza of the 'Deutschlandlied'.

The function of the Kampflied in the SA

Before looking more closely at Horst WesselL it is felt pertinent here to outline the function of the Kampflied in SA politics.

Practically all, if not all, SA songs before 1933 could be classed as Kampflieder, whose authors were usually members of the SA.

Given that the mass media as we know it today was at that time only in its infancy, the Kampflied still bore the important function of disseminating the philosophy and aims of any political (in this case the NS) movement, often through catchy slogans set to dynamic tunes played with much briskness and gusto. As Hans Bajer puts it:

'Das wirkungsvollste Propagandamittel für die SA war das Kampflied.

Wenn ein Sturm auf seinen häufigen Propagandamärschen singend durch die "roten" Stadtviertel zog oder an Sonntagen hinausmarschierte auf die Dörfer und Flecken, so stand das ganze Dorf im Bann der sangesfreudigen braunen Kolonnen.'

(‘The most effective means of propaganda for the SA was the Kampflied.

Whenever a Sturm on one of its frequent propaganda marches came singing through the ‘Red’ areas of the town, or marched out on a Sunday into the small villages and places, the entire village would be spellbound by the hearty singing of the brownshirt columns’)(Bajer 1939b: 586).

The messages incorporated in the songs were designed to appeal to the various sections of the community and to offer an alternative to what was perceived as the chaotic situation of the Weimar Republic:

'Das Kampflied sieht seine wichtigste Aufgabe darin, die Zeitgenossen auf die Bewegung des Führers hinzuweisen, ihnen einen neuen Glauben zu geben und das baldige Ende der augenblicklichen Not und Schmach anzukündigen.'

(‘The most important function of the Kampflied was to inform the public at that time about the Hitler Movement, to give them a new faith and to herald a quick end to the distress and ignominy of the moment...’)(Bajer 1939b: 587).

The concept of the mass movement, as promoted by the NSDAP, and the Kampflied are to be seen in close association, the latter serving the propaganda interests of the former.

In this regard it could be said that right from the very beginning, but especially towards the end of the Weimar Republic, the Kampflied was the embodiment of the song in action, or “Lyrik im Einsatz”, as the Nazis called it, to serve a given end.

The importance of the Kampflied in this context was evidently not lost on Horst Wessel either:

'Das Zaubermittel des gesungenen Liedes hatte auch Horst Wessel erkannt.

Es verging kaum ein Sturmabend, an dem er nicht ein neues Lied mit seinen Kameraden einübte, und in Berlin wußte man, daß sein Sturm die meisten und schönsten Kampflieder der Bewegung kannte.

Der sichtbare Erfolg blieb denn auch nicht aus: Horst Wessel hatte einen derartigen Andrang zu verzeichnen, daß sein Sturm 5 bald alle übrigen Berliner Stürme an Stärke überflügelte [cf. §1.1.above][...]. Das Kampflied war der Gradmesser für das Vorwärtsstürmen der Bewegung'

(‘Horst Wessel was also well aware of the magical impact songs could evoke. Hardly an evening passed with his Sturm when he would rehearse a new song with his comrades, and in Berlin it was common knowledge that his Sturm knew the greatest number of the Movement's best Kampflieder.

The inevitable success was for all to see: Horst Wessel scored such a success that his Sturm 5 soon surpassed all other Berlin Stürme in strength of numbers.

The Kampflied was the gauge whereby the Movement's surge forward in popularity was measured’)(Bajer 1939b: 587).

History of "Die Fahne hoch!" before 1945

According to Engelbrechten & Volz (1937: 90-91) “Die Fahne hoch!” was composed by Horst Wessel on the evening of 24 March 1929 following the first march made by the Berlin SA (Standarte IV - to which Horst Wessel then belonged) on that day via Bülowplatz (later Horst-Wessel-Platz, now Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz) and past Karl-Liebknecht-Haus.

As with other SA marches the intention, as mentioned earlier, was to provoke and draw out the opposition, and in expectation of an attack by Communists the Standartenführer is said to have given the order “die Reihen dicht geschlossen!” (‘the ranks tightly closed!’), which, according to Engelbrecht & Volz and “Rüdiger” (1933 quoting from a lecture delivered by Ingeborg Wessel), inspired Horst Wessel that night to compose his song.

The need for a song with a vibrant melody and an e'asy-to-learn and sing' text, that could be sung at the end of a meeting or march, as a balance to the “Internationale” of the Communists, was felt to be lacking in the SA repertoire (cf. “Rüdiger” 1933:).

The story goes that it was first sung at an NSDAP mass meeting in the Neue Welt-Halle some two months later (between 19-26 May 1929), at which Dr Goebbels was to speak. Standarte IV and the newly created Sturm 5, whose leader was Horst Wessel, stood behind the curtain waiting for the signal that Goebbels had ended his speech.

The applause had not yet died down when the curtain rose and the new song echoed round the hall ‘from 400 young throats’.

By the time the fourth quatrain (i.e. the first repeated) was reached the whole meeting had joined in the song (“Rüdiger” 1933).

According to “Rüdiger” and Engelbrecht & Volz (1937), the song was heard first on the streets of Berlin on 26 May 1929 (by Standarte IV and Sturm 5) following a æpropaganda march” to Frankfurt-an-der-Oder and found currency at the NSDAP Parteitage in Nürnberg 1-4 August that same year.

It was first sung at the Sportpalast, Berlin, at a mass meeting of the NSDAP on 7 February 1930.

After Wessel's death the song had already before 30.01.1933 took on the function of a Weihelied for the NSDAP, and after the “Machtergreifung” was elevated to the status of Party Anthem and as such played as an adjunct to the National Anthem, the Deutschlandlied (Oertel 1988).

However, Goebbels (Tagebuch 30.06.1937, quoted by Oertel) was of the opinion, somewhat belated, that in such circumstances the text would need to be modified, as it was felt to be unsuitable as it stood.

As it turned out, no modification took place - nor was it deleted (“Aber abschaffen kann man es nicht” (‘but one cannot do away with it’) - 30.06.37), and the text remained unaltered till the song fell into disuse after the end of the war.

As to the manner in which the song was to be sung, a regulation attached to a printed version of the song in 1934 made it clear that the right arm had to be raised (i.e. in a Hitler salute) whenever the first and fourth verses were sung.

In the pre-war years songs such as Horst WesselL, Deutschlandlied, and other popular patriotic and NS songs seemingly found free expression among street musicians, or in Gaststätten (bar restaurants), for example.

But in February 1940 as part of the official “Schutz nationaler Symbole und Lieder” (‘Protection of National Emblems and Songs’; in the context of the war situation) Goebbels, in association with the Interior Ministry, ordered the banning of such songs, including Horst Wessel Lied, in such as the above mentioned places, except on officially sanctioned special occasions.

The ban also covered the use of the melody with other texts.

In the case of the Deutschlandlied and the Horst-Wessel-Lied, these could no longer be played/sung in potpourris.

© Copyright Peter Crawford 2013

'Die Fahne Hoch'

Nürnberg Reichsparteitag - 1934

'Tag der Freiheit'

'Die Fahne Hoch' - Text and Melody

The Text

Although the song is believed to have been composed in March 1929, the first printed version of the text, so far as is known, did not appear till six months later in a supplement to Der Angriff Nr. 38 Berlin, 23 September 1929 entitled “Der Unbekannte SA-Mann”.

The text (see below) itself bears the title “Die Fahne hoch!”

This seems to be the original version of the song. The text is comprised of four quatrains, the fourth being a repeat of the first.

|

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2013 |

The street clear for the brown battalions, the street clear for the SA man. Already millions are looking to the swastika full of hope. The day of freedom and bread is dawning.

For the last time the rollcall has sounded, we are all ready for the fight. Soon Hitler flags will fly over barricades; the servitude will not last long now').

Notes on the Text

I.1. die Reihen fest geschlossen. This exhortation is not uncommon in songs of the period, cf. the 4th stanza in Weit laßt die Fahnen wehen by Gustav Schulten 1917:

Die Reihen fest geschlossen

und vorwärts unverdrossen

Kann er nicht mit uns laufen

so mag er sich verschnaufen

falle, wer fallen mag, bis an den jüngsten Tag.

(Uns geht die Sonne nicht unter. Lieder der Hitler-Jugend. Köln 1934:44).

l.2. Mit ruhig festem Schritt. As with the above, this is not a new creation, cf. the Andreas-Hofer-Lied (Zu Mantua in Banden), text: Julius Mosen 1831; melody: Leopold Knebelsberger ca. 1844, stanza 2:

Die Hände auf dem Rücken Andres Hofer ging

mit ruhig festen Schritten, ihm schien der Tod gering

der Tod, den er so manches Mal

vom Iselberg geschickt ins Tal

im heiligen Land Tirol

(cf. Allgemeines Deutsches Kommersbuch. Lahr/ScHorst Wesselarz-wald: Schauenberg 1966: 8-9).

I.3. Rotfront : meant here is the KPD, and possibly the USPD whom the Nazis suspected/feared might collude with the KPD. The SPD was seemingly regarded as “collaborators” with the Reichswehr.

Reaktion : meant here is the “Zen-trum Partei”; also the “Deutschnationale Volkspartei” and any other monarchist or separatist groupings.

Kameraden, die Rotfront und Reaktion erschossen: this line can also be read as active (which was also the case) as well as the intended passive.

I.4. Marschieren im Geist in unseren Reihen mit would refer not only to Kameraden killed in Berlin street fights and attacks, but probably also to the 16 who fell at the abortive putsch at the Feldherrnhalle, Munich, on 9 November 1923.

II.1/2. Die Straße frei... This would refer to the task the Nazis set themselves of “clearing” the streets of Communists, and others, in their “Conquest of Red Berlin”.

In the process people would see the swastika flags and (as the Nazis hope for) look upon them as a sign of better times to come, achieving "Freiheit und Brot”.

Barrikaden: : Street barricades were in evidence in Berlin during the early 1920s, but not so much thereafter or when Horst WesselL was composed (1929).

The reference is possibly meant figuratively, but probably for the reasons given above was quickly substituted.

III.4. Knechtschaft : meant here is probably the effects of the Treaty of Versailles (the so-called “Versailler Schandvertrag”) which set Germany under a heavy burden of reparations and associated difficulties.

The tenor of the song evokes a certain unity: with the flag raised on high as a symbol of the movement and its aims the troops (SA) in tightly closed ranks, including those who march in spirit (a notion of the dead assisting the living in the cause), remove the opposition, and in doing so offer a signal of hope to (as they see it) a beleaguered populace.

The “final battle” comes which the movement is confident of winning, after which the servility (as it is perceived) under which the country is suffering will be removed and a new dawning will arrive.

This motif of achieving victory through strife (common in songs extolling revolution) - in this context “for a New Germany” - is a reoccurring theme in many SA songs, e.g. Brüder in Zechen und Gruben (ca. 1927), Volk ans Gewehr (1931).

Metre and Linguistic Structure

|

© Copyright Peter Crawford 2013 |

The metre used is essentially iambic, with each quatrain having the pattern 51 5 61 5.

It falls into the pattern of the so-called “long metre”, reminiscent of the type: “O Danny boy, the pipes, the pipes are calling...”. A caesura occurs in each line after the second foot. ( • = short; - = long).

• - | • - || • - | • - | • - | •

Die Fahne hoch! Die Reihen fest geschlossen

|• - | • - || • - | • - | • -

S A marschiert mit mutig festem Schritt

| • - |• - || • - | • -|• - | • - | •

Kam'raden, die Rotfront und Reaktion erschossen

| • - | • - || • - | • - | • -

Marschieren im Geist in unseren Reihen mit

In “free metre”, i.e. in normal speech rhythm, we would expect the following:

• - • - • - • •/- • - •

Die Fahne hoch! Die Reihen fest geschlossen

- - • - • - • - • -

S A marschiert mit mutig festem Schritt

- - • • • - • - • - • - •

Kam'raden, die Rotfront und Reaktion erschossen

• - ( • )• - • - • - • -

marschieren im Geist in unsren Reihen mit

The melody (cf. § 3.5. below), however, has a slightly different schema.

It is simple in structure, in 4 4 (Common) time; the main stress/beat falls on the first element of the bar, with decreasing stress on the third, second, and fourth elements in that order, i.e. = 1, + 2, - 3, • 4 (the vertical single stroke | would here represent bar division). Thus we have:

|+ - • | = || • | = + - • | = -

Die Fahne hoch! Die Reihen fest geschlossen

+ - • | = || • | = + - • | =

S A marschiert mit mutig festem Schritt

+ - • | = || + - • | = + - • | = -

Kam'raden, die Rotfront und Reaktion erschossen

+ - • | = || • | = + - • | =

Marschieren im Geist in unseren Reihen mit

The result is that the main emphasis, resulting in elongated stress, occurs before before the caesura.

Given that the song is appellative to a specific group (i.e. the SA) recognisable slogans and Aufrufe would therefore be expected in places of emphasis, e.g. before the caesura: (I.1.) Die Fahne hoch! (I.2.) S A marschiert, (II.1/2) Die Straße frei! (III. 1/2.) Zum letzten Mal.

In the third line, the longest, the main emphasis comes on the second bar, with the highpoint reached in (I.3.) die Rotfront (which would be a term of abuse), (II.3.) Hakenkreuz, (III.3.) Hitlerfahnen, all meeting the appellative requirements of the song.

In I.3, however, the rhythm of the line requires unnatural stress on die (long instead of short). In II.4. Freiheit and III.4. dauert are split by the caesura, viz. Frei || heit, dau || ert, thus giving an unnatural and awkward emphasis, avoidable if sung in free rhythm.

As noted by Kurzke (1990: 128-29), Zum letzten Mal is reminiscent of the “last battle” motif found in La Marseilles and the Internationale, while the slogans Der Tag für/der Freiheit und für Brot bricht an (i.e. “Freiheit und Brot”) and Die Knechtschaft dauert nur noch kurze Zeit recall the concepts of “Knechtschaft”, “Reaktion”, along with the “Fahne” and “Kampf” metaphors, in 19th century Communist/Socialist Kampflieder.

There is also a certain amount of internal rhyme and alliteration used for effect:

I.2. marschiert mit mutig festem Schritt

I.3. Rotfront und Reaktion erschossen

I.4. im Geist in unseren Reihen mit

II.3. Es schaun aufs Hakenkreuz voll Hoffnung schon Millionen

II.4. für Freiheit und für Brot bricht an

III.1. Mal...geblasen

III.3. Bald flattern Hitlerfahnen über allen Straßen/Barrikaden

In addition the frequent re-occurrence of the /ai/ diphthong, through its high phonological profile, gives a greater zest and vitality to the song: Reihen, Geist, Frei, Freiheit, bereit, Zeit.

It is clear that some considerable thought has gone into fashioning it to achieve a desired effect.

We have seen the emphatic use of slogans and Aufrufe, found in lines 1, 2, and 4.

In contrast the third line of each stanza, i.e. the longest one containing six feet, makes use of the three tenses, past, present, and future, to give a sense of continuation and momentum to the song: (past) Kameraden, die Rotfront und Reaktion erschossen, (present) Es schaun aufs Hakenkreuz voll Hoffnung schon Millionen, (future) Bald flattern Hitlerfahnen über allen Straßen (cf. also Kurzke 1990: 128).

Along with skilful use of alliteration and internal rhyme, as we have seen, the final result cannot be said to be entirely devoid of some literary merit and quality.

The Melody

Melodic analysis

Melodies A and B are identical. The pattern of the phrases is typical of the Lied style.

In B bars 2b-3a correspond exactly to the opening and imply a sequential phrase, but 1b-2a and 3b-4a negate this. Bars 4b-6b are characteristically at the highest pitch, and with the final phrase returning to the key note.

3.5.3.2. Implied harmonic framework

An implied harmonic framework could be sketched as follows:

bar 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

implied I IV V I I IV Ic V I

Harmony

It is quite possible to use only the three basic chords of I, IV, and V to harmonise the melody satisfactorily. Bars 3-4 are sequential to bars 1-2, as was implied, but not fully carried out in the melody.

The final cadence of Ic V I is characteristic of Northern European music from the Baroque period onwards.

There is no sense of implied modulation.

Rhythmic structure

The rhythmic structures are very similar, with only a small modification in B.

Each phrase begins on an anacrusis, leading to a longer note on the first beat in bars 1, 3, and 7. Bar 5 reflects this but with a dotted note of shorter value. However, bar 5 has greater movement, with a note on each half-beat.

Bars 6b-8a return to the original pattern.

B uses more dotted rhythms, as in bars 1b, 3b, 5b, and 7b.

In Western European tradition these often have a military implication of an heroic nature, cf. Beethoven's "Eroica" Symphony (No. 3), Slow Movement - Funeral March.

______________________________________

HORST WESSEL and HANNS EWERS

In an editorial in the Völkischer Beobachter, Alfred Rosenberg (see right) wrote of how Horst Wessel was not dead, but had joined a combat group that still struggled with them; and afterwards, members of the NSDAP spoke of how a man who died in conflict had joined "Horst Wessel's combat group" or were "summoned to Horst Wessel's standard."

In an editorial in the Völkischer Beobachter, Alfred Rosenberg (see right) wrote of how Horst Wessel was not dead, but had joined a combat group that still struggled with them; and afterwards, members of the NSDAP spoke of how a man who died in conflict had joined "Horst Wessel's combat group" or were "summoned to Horst Wessel's standard."

When the Third Reich was established in 1933, an elaborate memorial was erected over the grave (see left), and it became the site of annual pilgrimage, at which "Die Fahne hoch" was sung, and speeches made.

Horst Wessel was also commemorated in memorials, books and films.

for more information about

Hanns Heinz Ewers, another supporter of the Welteislehre, wrote a novelistic biography of him.

One of the first films of the Nazi era was an idealised version of his life, based on Ewers' book, although the main character's name changed to the fictional "Hans Westmar".

|

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2013 |